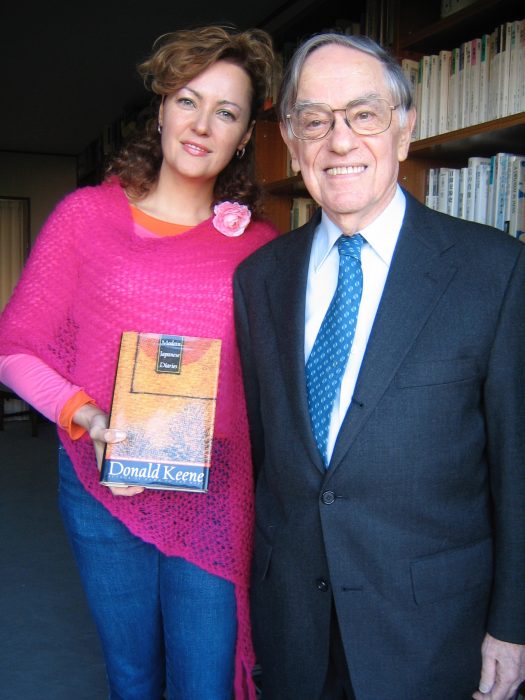

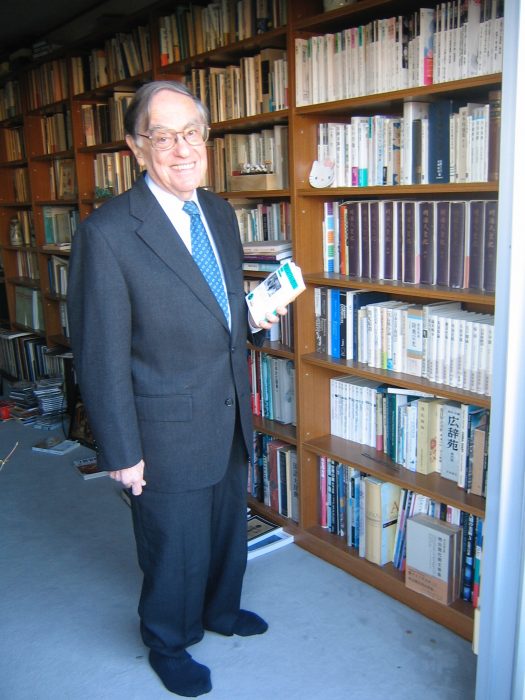

Others: Author Donald Keene

Scholar of Japanese literature, Professor Donald Keene, interviewed by Judit Kawaguchi in 2006.

For someone interested in Japan, it is impossible not to encounter Donald Keene at some point, and usually soon, at many places and very often. And what a great pleasure it is, every time.

Want to know about bunraku, the art of the Japanese puppet theater? In 1965 he wrote an informative and fun book about it. Would like to get acquainted with the masterpieces of Japanese literature? His fantastic anthologies will transport you from the earliest era to the 20th century in great style. And if you already love the writing of Yukio Mishima, then you probably read it in his beautiful translation.

For his tireless efforts to bring the wonders of Japanese literature and culture to people around the world, he has received numerous awards, including the Order of the Rising Sun from the Japanese government and another one of Japan’s highest honors, when in 2002 he was named a Person of Cultural Merit ( Bunka Koro-sha.)

That same year his biography of the Meiji Emperor won the Mainichi Shuppan Culture Prize and in 2003 he was honored with the PEN/Manheim Medal for Translation, given to a translator “whose career has demonstrated a commitment to excellence through the body of his or her work”. Keene has done just that and he began when it was not yet hip to be interested in anything else but Western civilization.

“When I was a student in New York, we studied history but it meant Europe only. We also learnt about the U.S., but nothing about the rest of the world. Now kids read about other civilizations, too. I am happy that culture is not just European anymore.”

Keene had contributed greatly to this change. It was in 1931 that he realized for the first time how important it was to learn foreign languages.

“I was nine years old then and we went to Europe with my father. Once we were back in New York, I asked him to hire a private tutor so I could start French lessons. Unfortunately those were such hard times that my parents couldn’t afford a teacher and I could only begin French in junior high school, at age 12.”

This might sound late to many, especially in Japan, where nowadays the trend is to teach Japanese children English as early as possible, often simultaneously with their mother tongue. “I am sure it is wonderful to grow up with two or more languages although some find it that this develops a split personality but from my point of view it would have been a blessing. The more languages one knows, the more interesting life is.” He should know: his desire to acquire knowledge lead to many adventures.

“I was 14 and learning Spanish, too because my father was in Spain on business and we were going to move there but in the summer of 1936 the Spanish Civil War broke out and we ended up staying in New York. I continued with French and Spanish and at sixteen I graduated high school and entered Columbia University on a scholarship. I was still under the influence of my high school teacher who recommended me to read literature in its original language so she wanted me to learn Classical Greek, Latin and German. But at Columbia, I could only take 2 foreign languages in my first year so I did German only as a senior. I didn’t get a good grasp at that time and although I studied it again later on, my German is still not very good.”

It was in January of 1942, at age nineteen, that he graduated Columbia University and enlisted in the navy. “I studied Chinese at Columbia and added Japanese at the U.S. Naval Japanese School in California. There I also discovered that I really liked the company of Japanese people so once the war was over in 1945 and my service in China ended, I took advantage of the fact that the plane stopped in Japan and spent a week here. After the war, other translators and interpreters gave up Japanese but I liked it too much. Also, I didn’t want to be the 100th person to translate Moliere or be stuck with a subject like “The reputation of Chaucer in Spain.” With French or Spanish, sooner or later I would have had to choose a topic like that because even by then there were too many scholars of European literature. Japanese was so intriguing and I was excited to do something very few people did before me. The great Arthur Waley was the only predecessor whose translations I loved but there was a lot he has not touched yet.”

With a clear goal to become a scholar of Japanese, Keene returned to Columbia University for graduate studies and PhD work and after teaching Japanese at Cambridge University, he came to Kyoto in 1953 and stayed for 2 years to compile the first of his many anthologies of Japanese literature.

“There are immense connections between any language and its culture. Language reflects the customs of people and their culture. When one learns Japanese, one is surprised by the different levels of politeness which is so special to Japanese. There is almost nothing like a neutral statement. You must always indicate your feelings towards the person you are talking to, to show the difference in social status. Sometimes you are too polite or not polite enough. In English we use the same verb “is” or “eat” for a dirty dog on the street and god, but in Japanese the verbs are completely different. So you see that there is certain vagueness in the Japanese language: they love blurry outlines.”

He guesses that he must have written about forty books in English and maybe fifty in Japanese. In 1955, after two years of living in Kyoto, he became a professor at Columbia University but each year he has been spending his holidays researching and writing in Japan.

“In the beginning I came for three months or so but that was just not long enough for all the work. So from 1980 till my retirement in 1992, Columbia allowed me to teach half a year, which is four months, so I could spend eight in Japan.”

He is still teaching a one-month course at Columbia and lives most of the year in Tokyo.

“I am like a Japanese person in a sense but that doesn’t mean I know every kanji character or word. Japanese is not one language: a dialect is almost like another language and Japan has so many wonderful dialects. People in Kagoshima, Aomori, Osaka or Kyoto speak dialects so special that if we wanted to learn them, it would not be too different from mastering a foreign tongue. Sometimes it is easier to speak a certain way when you put on special clothes. I studied kyogen in the 1950’s and saw children of actors dress up in traditional garb and suddenly they were talking in 17th century Japanese, not their usual kid language.”

He thinks unfortunately today’s Japanese children know a lot less about their culture than their parents did. “This trend is true all over the world but particularly acute here. If the emphasis is on English, they will lose Japanese: it is inevitable. Children should have a strong foundation in their own language and culture but sadly here the direction is not towards gaining a good understanding of Japanese history, philosophy and literature. The Japanese should be proud of their wonderful stories. When kabuki first went to the US in the 60’s, members of the Diet said that no play should be shown if it contained feudal ideas or women of the licensed quarters. This eliminated almost the entire kabuki repertoire. I hope that today Japanese realize how silly this idea is.”

Keene is an advocate of a more active promotion of Japanese culture because he thinks it is world-class and can enhance people’s lives all over the globe. “The Japanese should recognize how attractive their culture is but instead they always worry that it is so special and strange that no foreigner can ever get it. We do, many of us.”

The huge variety of events and lectures at the Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture at Columbia University, opened in 1986 and named in his honor, is proof that he is right.

“We have lectures and exhibitions on both classic and contemporary topics and the interest is immense. We have full houses for the lectures, many of which are given in Japanese.” Keene has been working relentlessly since the 1950’s at publicizing Japanese culture abroad.

“The Japanese are great at many things but they are very weak at self-promotion. I think the Japanese government should copy the French who are masters of self-promotion. The reason people love French culture is because the French government spent an awful amount of money on cultural exchanges.” Keene is doing his part and his latest book, due out in the U.S. on May 5th, is an investigation into the life of Watanabe Kazan, the famous portrait painter.

Keene loves the Japanese artistic sensitivity and recommends artworks as an easy access point into the depth of Japanese culture. “If you go to any department store, visit the section where they sell pottery and things made of wood or steel. The artistry of the Japanese is astonishing, the number of things they do beautifully and also the number of people who make a good living in this country as potters, painters, artists, is a lot more than anywhere else. These artisans can survive and thrive because the average Japanese has a heightened sensitivity to beauty and is willing to spend lots of money on these artistic items to support the artists.”

He thinks this strong sense for beauty can also be acquired through language. “Read a Japanese letter and the first part is always about the seasons, the pretty autumn leaves or the cool wind blowing. They love nature and want to share its wonders with others. Everyone in the world likes a pretty flower but the Japanese carry it to another level: they have an emotional reaction to beauty. Learning Japanese will help you get this.”

Keene discovered many more aspects of himself through language study. “Once you speak another language, you realize new things inside yourself that you didn’t express before. These are the things that come out better in another language. For example, for me the word “sabishii” is like that because I know exactly what sabishii is but I don’t know how to say it in English. I could say lonely but it doesn’t give the full quality of sabishii.

Another is arigatai, which means to be grateful for, but it has so many other ways of use. Mottainai is also very difficult, since it can mean something quite wonderful or too good for you, so the meanings are contradictory depending on the context. I experienced this when I worked on Tsure zure gusa, a 14th century book of essays, which I translated as Essays in Idleness. The book is beautifully written but he uses the same adjective over and over again, one that doesn’t exist in modern Japanese, “imijiki,” and each time it appears the translator must decide what the right meaning is in a particular sentence. It can mean wonderful, frightening, or terrible, so a translation machine could not manage such an assignment.”

Even with modern texts he encountered similar problems. “I was translating a novel by Yukio Mishima and there is a scene that takes place in a fashionable restaurant and the proprietress is very careful as to how she talks to her customers. She only teases the very successful ones who do not mind such jokes. Mishima used the expression the she said “bureina koto” to one man, which is a sort of impolite, teasing expression. I could not think of the perfect word till a month later when I arrived in Angkor Wat and as I stood in front of the magnificent statues, I thought of the right word: uncomplimentary. Luckily I was still able to edit the book.”

Although Professor Keene would rather see children reading Saikaku and not just manga, he is hopeful: “Most people who love literature will come to it naturally, even if they are not encouraged. But learn, and do as much as possible, while you can, because as one grows older, it is harder to remember things.”

A version of this interview appeared in Select magazine in February 2006.

This QuoteThe Japanese should be proud of their wonderful stories. — Donald Keene